Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Beginning in September of 2019, major retail brokerage firms dropped their commissions to zero. Although other players had previously offered trading for free, the sudden move to zero seemed shocking. On reflection, however, this move was the natural progression of regulatory and competitive forces over the course of decades.

Now that zero commissions are part of the landscape, it is important to understand how we got here and what to expect next. Greenwich Associates believes that the future looks bright for retail traders, although attention needs to be paid to how retail brokerages continue to monetize those relationships. We also examine the role of the market maker in providing services to retail brokers.

Overall, we find that it has never been better for the retail trader, which is not likely to change in the near future.

Introduction: Never Better

For over a decade “the retail investor has never had it better” has been a common refrain.¹ During that time, fierce competition for retail order flow, regulatory reform benefiting retail traders, and commission cost compression have all drastically improved the trading and execution of retail orders. In addition, most of the largest brokerages recently dropped retail commissions to zero. This change, in hindsight, was a long time coming. However, the ramifications of such a major market structure shift are an intense point of scrutiny.

On the whole, Greenwich Associates finds that retail investors, in fact, have never had it better. Not only have their commission costs come down to zero, but the services they receive have never been more advanced. Years ago, retail investors had to call their brokers and hope that their calls were answered in order to get a trade done. Now, retail investors enjoy many of the advanced tools and capabilities previously reserved for professional or institutional investors. These systems include sophisticated charting options, customizable filtering for trade opportunities, tremendous amounts of data at their fingertips, and even the ability to program some of their own trading strategies. We have also seen execution venues continually innovating and regulatory changes increasingly favoring the needs of retail traders.

Moreover, execution quality metrics have continued to improve decade over decade.

Significantly, we find that today’s market makers are providing execution quality at the highest levels. While payment for order flow amounts have shrunk year over year, commissions have still dropped to zero. That said, we do not see the focus on retail brokers’ and market makers’ best execution requirement slackening, even while the explicit compensation for doing so declines.

We believe that retail investors will continue to receive tremendous attention from their providers, who will continue to enhance such services. Why do we believe this? Because the markets have decades of history that show increasing service and improving execution to retail traders.

To that end, it is an opportune time to look back at the evolution of retail equity trading in the United States in an effort to better understand where the market is likely headed in this new, post-zero-commission world.

35 Years of Regulatory Reform

There are (at least) four seminal regulatory events over the past few decades that have shaped today’s retail trading experience.

First, the world changed in 1975 when the SEC abolished fixed commissions, opening the door for the now ubiquitous discount brokerages. Prior to May Day, commissions on trades were very expensive, often in the hundreds of dollars per trade.

Second, the SEC’s rule for Disclosure of Order Handling and Routing Practices was approved in November of 2000. Disclosure of this information allowed apples-to-apples comparisons among brokers for the first time. Investors, their brokers and the regulators were able to compare a variety of data on order execution across sizes—for equities and options—and were provided at least some amount of information regarding economic relationships among the parties. With that data now public, regulators have become increasingly focused on execution quality, requiring brokers to continuously justify their routing decisions based on their obtained results.

Third, on April 9, 2001, all U.S. equities began trading in pennies and moving away from fractions, which had been the practice for the prior 150 years. In an instant, the minimum spread cost for trading dropped orders of magnitude, from trading in 1/16ths (or $0.0625 cents per share) to $0.01, an 84% decrease.

Last but not least, the adoption of Reg NMS, in particular the introduction of the Order Protection Rule (OPR), meant that retail orders were given even more protection than before. For example, whereas block trades might have previously traded through retail orders displayed in the market, post the OPR, such orders were “protected” against such trade-throughs (at least insomuch as they resided at the top of an exchange’s book).

Regulators didn’t stop there. Oversight of trading by market intermediaries has also been greatly increased over the past several decades. Throughout these years, the SEC’s Section 21(a) Report on NASD, the Nasdaq market-maker collusion scandal and the NYSE Specialist Execution Fraud Settlement all resulted in enhanced retail investor protections and an augmented regulatory oversight regime.

Competition is Good

Competition has also been a huge driving factor in the lowering of commissions over time. Much as the original discount brokers challenged the incumbents with lower commissions starting in the mid-70s, the mid-2010s brought about a new breed of retail trading—generally offering low or zero commission through app-based trading. From Robinhood in 2013 to Webull in 2017, these companies advertised themselves more as technology firms—not just brokers—appealing particularly to the millennial crowd and their associated distrust of old-school Wall Street. The major players made multiple steps toward zero commissions to compete: Some offered a set number of free trades per month, but only to their best clients, while others offered free trading on a limited universe of ETFs. It just wasn’t enough, however, and the pressure to go lower became unrelenting.

In what now seems like a natural progression, Interactive Brokers offered a zero-commission product in September of 2019. The other large discount brokerages quickly followed suit—Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade, E*Trade, Fidelity—along with larger institutions, including some bank platforms. Today, zero-commission trading for retail is the norm.

The Role of Market Makers

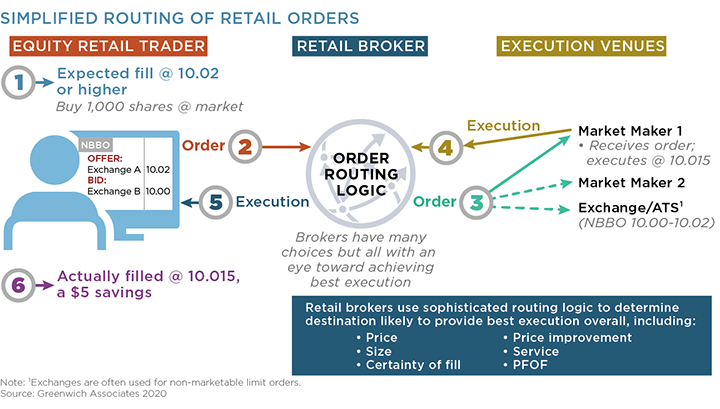

Nearly all retail broker-dealers send the overwhelming majority of their “non-directed” orders—those not designated to go to a specific venue—to wholesale market makers such as Citadel Securities, Virtu, Susquehanna, and Two Sigma. These market makers compete intensely to win order flow from retail broker-dealers by delivering “best execution” to the end retail investor.

So, what is basis of this intense competition among market makers?

Primarily, market makers compete through their ability to provide best execution, often through price improvement to retail orders.² Quite simply, they can often provide better prices than that available from the exchanges’ public quotes. The amount of this price improvement can be quite significant. In fact, public data shows that market makers provided an average of $6.18 in savings per order during 2018.³ This amounts to over $1.3 billion in savings to retail investors versus orders routed to the public quote. Moreover, nearly all retail-sized orders⁴ received price improvement from market makers. Rule 605 data shows for the period July 2018–June 2019:

- 87% of retail market order shares received price improvement

- 94.9% of retail market order shares executed at the NBBO or better

Critics complain that the practice of brokers accepting payment for order flow (PFOF) influences routing practices. However, PFOF is very similar to the rebates that exchanges pay for execution of non-marketable limit orders in their venues.⁵ In addition, more than half of all retail broker-dealers do not accept PFOF. Firms that do accept PFOF have strict best execution regimes that require them to send orders to the destinations providing best execution, whether market maker, exchange or dark pool, not simply where PFOF is highest. Finally, PFOF has remained stable or even decreased over the past several years, while price improvement given to retail orders has increased more than four times during that same period. Today, the average PFOF per share is approximately 1/8 of the average price improvement per share.

Of course, with market makers providing so much price improvement as well as PFOF on some orders, how are they able to be profitable? The answer is simple—the characteristics of retail order flow make internalization a statistically valuable exercise. Retail orders are generally not oversized to the market (unlike institutional orders which may be multiples of market size or even ADV of a security). The risk for a market maker to internalize against such smaller orders is much less than against orders that can overrun their risk appetites. Further, the majority of retail orders do not have an informational advantage as compared to the market maker. Therefore, the market maker can internalize these orders to earn the spread, less their costs of obtaining the flow. Market makers can also trade with retail orders to naturally enter or exit positions, creating additional liquidity for the market.

Market makers can also use retail order flow as part of a larger hedging strategy across different asset classes. That said, while the concept of handling retail order flow is simple in concept, it is extremely challenging in execution. As price improvement requirements have risen and spreads have fallen, a number of market makers have exited the business. The remaining firms have had to make considerable investments in infrastructure, technology and talent in order to remain competitive. They have also had to ensure that their balance sheet can weather fluctuations in trading, where their net revenue is often a fraction of the total payments made to obtain the flow.

In light of this competitive environment, one possible challenge in the zero commission world is whether professional traders enter the market via these channels and change the nature of retail order flow.⁶ Over the past decade, the average price of stocks has continued to rise, and stock splits have become more rare. When more than half of all trades are in odd lots in NMS securities,⁷ orders representing over $100,000 of value may not even be a round lot in certain securities. In this environment with zero commissions, there is a concern that the mix of order flow from retail brokers could become tilted toward more professional flow rather than true retail. If this comes to pass, the markets will have to determine if differing designations and treatments should be applied to professional versus retail flow in the equities markets.⁸ One major concern would be if professional traders captured a disproportionate amount of pricing improvement intended for retail traders, which could have the effect of negatively impacting the retail trading experience. We will continue to watch the evolution of this dynamic closely.

It must also be noted that the exchanges and their display of the public quotation are undoubtedly good for the market as a whole and for retail traders in particular. Without the NBBO to establish the proper price, the retail brokers would be hard pressed to justify their routing to the market makers. At times, concerns are raised that there is too much execution occurring in the dark, thereby impacting the public quote. However, data shows that the spreads on the most-liquid names have remained remarkably stable, other than in response to macro-market events like the financial crisis.⁹ Certainly in thinly traded securities and high-priced stocks, the markets need to remain diligent to ensure that the public quote remains the proper benchmark for trading, internalized or otherwise.10

Staying in Business While Charging Nothing

Historically, although retail brokers make money on commissions,¹¹ other services provided to their clients also generate significant revenues, such as:

- Interest on monies held with the broker (minus any interest paid to the client)

- Rehypothecation of securities held by the firm

- Borrowing charges for clients selling short

- Other account fees (inactivity fees, account minimums, etc.)

- Interexchange fees on credit/debit card

- Payments for money sweeps to program bank

- Payment for order flow

Many of these services operate on economies of scale. The more assets that firms have under their control, the better. Consolidation will be a natural evolution, as evidenced by the recently announced proposed $26 billion acquisition of TD Ameritrade by Schwab and the $13 billion acquisition of E*Trade by Morgan Stanley.¹² Other firms are likely to be targets as well.¹³

The largest retail brokers already have considerable “pricing power” in the requirements they seek from their market makers. Will we end up with only a few of these behemoths on the retail trading side? Again, a bit of history sheds some light here.

Prior to the introduction of electronic communication networks (ECNs) in the marketplace, and the ability of firms to trade more freely over-the-counter, costs of trading on exchanges were relatively high and innovation, particularly in technology, was not a significant driving force. Veteran traders will well remember the fears of there being a duopoly of only Nasdaq and NYSE. The concern was that such a limited competitive environment would lead to excessive pricing power by the exchanges and limited investment in innovative technologies. Those fears were proven overblown, with a surge of new venues coming into the market to drive change. Subsequently, there was a round of consolidation, reducing the majority of the exchanges to three main groups. Today, we see another round of new exchange entrants coming into the market. And so it goes.

Although today’s retail brokers may consolidate into a smaller number, competitive forces and the threat of new entrants will prevent them from exerting excessive pressure on their market-making providers. Similarly, if brokers fail to meet the needs of their clients, other firms will undoubtedly seek to capture their business, enabling yet another round of innovators to bring their ideas to the market.

Can It Get Any Better and What Are the Concerns Going Forward?

It might seem we have reached the apex for retail investors, and that it couldn’t get any better. But there is still room to move their experience forward. Retail brokers will continue to provide differentiating services and develop new tools for their clients.

Of course, one possible negative of the zero-commission story would be if the retail brokers dial down the services and technology offered to their retail clients. However, we firmly believe that competition will require these firms to reestablish their value continuously. Of course, they may well offer additional services to these clients in order to provide value, and those new services will likely come at a cost.

Another concern is whether or not the move to zero commissions will impact the execution quality provided to retail orders. Retail brokers have long touted their execution statistics. The post-zero-commission world has not proven any different. Firms still use their best execution statistics as a primary selling point, which means they will still have to seek best execution from their market makers and other destinations. As such, it is almost certain that execution quality demands will continue to be at the top of their list. Regulatory pressure and customer demand will also act to maintain execution quality standards.

We believe that even if there is a temporary over-concentration of retail brokers through consolidations, market forces will breed new entrants. If that happens, both the services offered and the execution quality provided will prove that trading is, again, “better than ever for retail traders.”

1See, e.g., https://www.businessinsider.com/the-market-has-never-been-fairer-for-the-retail-investor-2009-7; https://abnormalreturns.com/2012/02/14/there-has-never-been-a-better-time-to-be-an-individual-investor/; https://www.businessinsider.com/historical-trading-commissions-2014-3; https://www.sec.gov/spotlight/emsac/testimony-steven-quirk-td-ameritrade.pdf; https://finance.yahoo.com/news/investors-never-better-despite-trade-war-populism-132910423.html

2Other important considerations are enhanced liquidity, speed of execution, certainty of execution, ability to handle trade accommodations, and customizations for individual clients’ order flow.

3Public 2018 SEC Rule 605 data.

4Orders sized 100–9,999 in total shares.

5In maker/taker exchanges. In taker/maker exchanges, the rebate is paid to the firm that executes against the resting limit order. Other than that inversion, the underlying economics are similar, although the resulting trading behavior is often very different.

6Indeed, recent data indicates that, at least for now, retail trading has increased fairly significantly. TD Ameritrade reported a 40% increase in trading volume post the zero commission move, while E*Trade noted a 21% increase in trading volume in the 4th quarter over 3rd quarter 2019.

7The SEC MIDAS’s system data shows that odd lots trades exceeded 50% in NMS securities and 30% in ETPs as of September 2019. See https://www.sec.gov/marketstructure/datavis/ma_overview.html#.XgeyZxdKglI and https://www.greenwich.com/equities/investors-take-market-structure-issues-20192020.

8There are various methods that could be used to delineate between retail and professional traders, such as the professional trader designation in the options markets or the retail definition in certain exchange programs.

9See, e.g., http://www.q-group.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Equity-Trading-in-the-21st-Century-An-Update-FINAL.pdf.

10The SEC has recently sought comment on how the market might be able to address some concerns related to thinly-traded and high-priced securities, including, among other ideas, the possibility of changing tick sizes on high-priced stocks, adding odd lots to the SIP feeds, suspending UTP privileges to centralize trading of thinly-traded securities, or some combination of these among other various proposals. https://www.sec.gov/rules/policy/2019/34-87327.pdf

11For example, commissions comprised about 7-8% of Schwab’s revenues, 17% of E*Trade’s revenues, and approximately 30% of TD Ameritrade’s revenues.

12Not that these deals are necessarily a foregone conclusion. Both regulatory and anti-trust approval will have to be obtained for them to be consummated. However, if approved and consummated, it is estimated that the Schwab-TD Ameritrade firm will have $5 trillion in client assets and the Morgan Stanley- E*Trade firm will have $3.1 trillion in client assets.

13For example, firms such as Robinhood would appear to be an interesting target, particularly for the client base, although the recent valuations may be considered rich with zero commissions now being the norm. It will be very interesting to see how valuations might change over time in response to this change.