Table of Contents

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) under Chairperson Gary Gensler has once again proven itself to be quite imaginative and industrious, as the agency turns to the U.S. Treasury market as another outlet to channel sweeping changes to the financial markets. On March 28, 2022, the Commission proposed a pair of rules aimed at principal trading firms (PTFs) (or “prop” trading firms), which provide liquidity and other dealer-like functions. In short, these firms would be required to “register with the SEC, become members of a self-regulatory organization (SRO), and comply with federal securities laws and regulatory obligations”.1

It’s no state secret that the SEC has long desired to regulate the likes of prop shops active in the U.S. Treasury interdealer market, as they provide similar offerings as primary dealers. In some cases, these firms offer liquidity via registered broker-dealers, alleviating any regulatory impact from the proposed rules.

However, the breadth of the rules could still get under some market participants’ skin. According to the SEC’s release, if adopted, the proposed rules—also known as Exchange Act Rules 3a5-4 and 3a44-2—offer further definition and insight into the phrase “as a part of a regular business” in Sections 3(a)(5) and 3(a)(44) of the Act. In English, that means some activities that may be part of a normal course of business could be construed as dealer-like and, hence, subject to the new rules.

Human Sacrifice! Cats and Dogs Living Together? Mass Hysteria!

A buy side and a sell side—the two sides of the market—coexist. The sell side offers liquidity and the provision of credit to buy-side firms, which in turn leverage these services to invest on behalf of their clients. The interdealer community serves the sell side with additional liquidity resources, data and network—a market structure that’s held up well beyond the “Five Families,” despite technological advancements.2 The scope of the non-dealer registration rule challenges this structure, as it presents a case for treating buy-side firms as if they were dealers. Generally, you don’t see the need for that type of requirement in well-behaved markets. Yet, here we are.

In the eyes of the SEC, the identification and registration of firms that contribute significant market volume and engage in dealer-like activities would enhance market stability and investor protections by increasing oversight. However, it is clear the Commission may not appreciate how far the proposed rules go, as well as their potential for tearing down a functioning market structure in U.S. Treasury securities. For instance, some private funds and investment advisors could be dragged into the regulation because they trigger the threshold requirements.

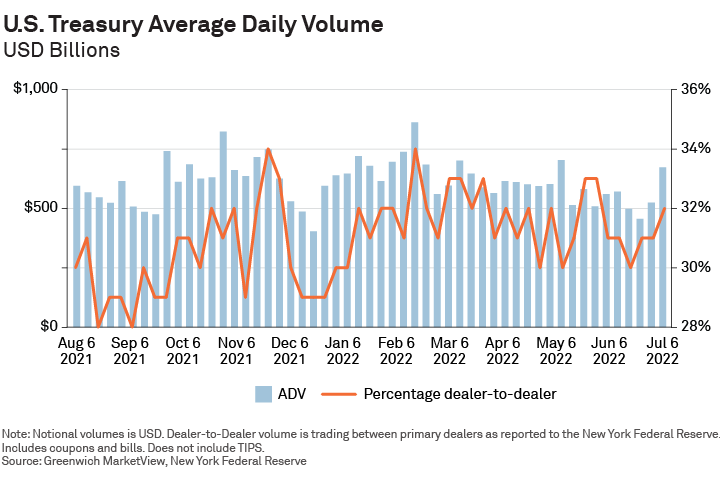

Under Rule 3a44-2, transacting in more than $25 billion of trading volume in U.S. Treasury securities in four out of six calendar months is determined to be “a part of regular business” and subject to the proposed rules. According to market participants we spoke with, the threshold is intentionally low to capture any firm attempting to restructure their business to circumvent the rules. New York Federal Reserve data seems to confirm this, as average daily volume often well exceeds $500 billion on a given day. If $500 billion traded each day, $40 trillion would trade over the course of four months, assuming 20 trading days per month. $25 billion represents a mere 0.0625% of that amount.

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

While there are some exceptions to Rules 3a5-4 and 3a44-2, including exemptions for persons having or controlling less than $50 million and firms already registered under the Investment Company Act, one can envision numerous investment advisors and larger hedge funds triggering the threshold—the result of which would lead to many unworkable conflicts. The likelihood of unexpected consequences scales up when the following examples are taken into consideration:

- Competing regulations would result in material impact and inconsistency on the buy side: Dealers are governed by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) rules, which prohibit them from participating in the IPO markets, for example. During 2021, 1,073 companies IPO’d, raising $317 billion, according to FactSet data. In the first half of 2022, a total of 92 companies raised $9 billion as stocks swooned, interest rates rose and the SPAC bubble burst.3 Restricting hedge funds from access would have a material negative impact on both the hedge fund business and general liquidity in the IPO market—particularly in the current market environment.

- Once a customer, no longer a customer: The designation of “dealer” implicitly means a firm is no longer considered a customer under SEC rules. This has myriad implications stemming from the loss of customer protections the Commission has designed, including counterparty defaults where a dealer would not receive the same bankruptcy protections as a buy-side firm. From a fiduciary standpoint, this appears to be a non-starter and would hinder investment as well as the diversification benefits of different styles and strategies with a reduced set of buy-side market participants.

- U.S. Treasury market liquidity could suffer: It’s possible to envision PTFs registering as dealers and continuing their business. However, it’s likely some could shutter or scale back their trading to fall below the threshold, creating a more concentrated group of firms active in the interdealer market. Presently, PTFs account for roughly 19% of interdealer volume, according to SEC data in the release. Form PF recorded data collected in the second quarter of 2021 points to 1,968 hedge funds that qualify under the rules (roughly 20% of total firms reporting positions via Form PF). Their positions consist of $1.7 trillion in U.S. government securities.4

Remaining in Limbo

Market participants are in a holding pattern since the comment period came and went on May 27, 2022. According to the comment log, the ratio of nays and yays was 30:1, prompting investors to wonder who exactly this rule is intended for. Certainly some dealers may find Rule 2022-54 desirable since PTFs are competition. Firms providing similar services should be regulated in a similar manner where appropriate—most people “get” that. However, it’s unlikely banks and dealers want to lose mid- to larger-sized buy-side clients in the process as part of the Gensler metamorphosis.

As the weeks and months pass, it is imperative that the SEC study the effects of liquidity drain in the market for U.S. Treasury securities and consider what withdrawal by major market participants might look like. For instance, at the end of 2021, according to the U.S. Treasury, holdings totaled $7.75 trillion. Regionally speaking, positions tied to the Cayman Islands—where many U.S. hedge funds are domiciled—accounted for about $269 billion or 3.4% of the total.

Would liquidity change in the market if the eighth largest holder by region shrunk alongside waning PTF participation? What would less participation mean for bid-offer spreads? How would less liquidity impact retail consumers? There are so many unanswered questions.

Audrey Blater is a senior analyst focusing on risk and capital markets regulation on the Market Structure and Technology team.

1https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-54

2The Five Families refers to the five dominant interdealer brokers that provided the majority of liquidity between sell-side firms into the 2000s.

3https://insight.factset.com/u.s.-ipo-activity-drops-dramatically-in-the-first-half-of-2022

4Form PF data is limited to SEC-registered advisors with at least $150 million in AUM.

MethodologyDuring Q3 2022, Coalition Greenwich interviewed several U.S. buy-side and sell-side institutions to gain their qualitative feedback in relation to the proposed Exchange Act Rules 3a5-4 and 3a44-2.