Table of Contents

- 1.Many Asian companies were prepared for tariffs

- 2.Asia-based corporates hold off on price increases—for now

- 3.Unexpected benefits: Lower prices in some Asian markets

- 4.Unintended consequences: De-dollarization gains steam

- 5.Second-order effects: U.S. banks losing traction

- 6.How can banks help companies navigate tariffs?

- 7.Tariff upheaval slows trade finance digitization

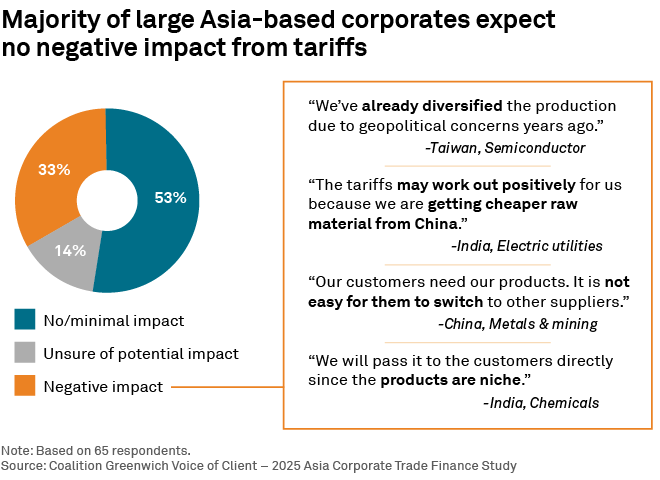

While new tariffs imposed by the United States are top of mind for many large Asia-based corporates, many are choosing not to react prematurely. There are several reasons for this. First, large Asia-based corporates that have low exposure to the U.S. are not yet seeing adverse impact on their businesses. For companies that do business with the U.S., some see their products as having relatively inelastic demand in the short to medium term. In the words of a treasury official from a Chinese metals and mining company, “Our customers need our products. It is not easy for them to switch to other suppliers.”

Furthermore, many large companies in China have already taken measures over the past several years to divert a portion of their exports to new markets and scale back ties with U.S. banks. This was a trend that started back in 2018, when the first Trump administration imposed its initial 25% tariff on Chinese goods.

There is one important exception to that trend: Companies in countries that did not expect to get hit with sizable tariffs. South Korea is one example. Across Asia, approximately one-third of large corporates say new trade tariffs will have a negative impact on their businesses in the next six to 12 months. In South Korea, that share jumps to a full 60%.

South Korean companies were blindsided in April 2025, when the U.S. announced a 25% tariff on most South Korean goods, with even higher rates for certain sectors like steel, aluminum and copper. Although the South Korean government ultimately negotiated the tariff rate down to 15%, even that new duty represents a significant change to the export business models of South Korean companies. Because they had not anticipated tariffs at this level, these companies had not taken steps to diversify their businesses and operations—a strategy that has been pursued aggressively by companies in China and other Asian countries.

A similar scenario is playing out today in India. On August 27, the U.S. increased the tariff rate on Indian goods to 50%, after we had completed interviews for our 2025 Asia Corporate Trade Finance Study. While the exact number of companies negatively impacted by tariffs in India is not yet known, we expect the percentage to be high.

Many Asian companies were prepared for tariffs

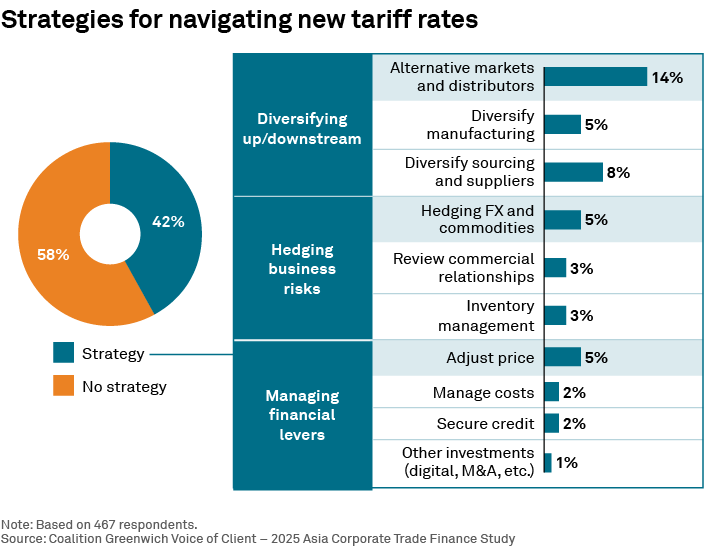

The fact that more than half of large companies across Asia believe new U.S. tariffs will have little or no impact on their businesses reflects the steps companies have already taken. More than 40% say they have implemented strategies to mitigate the effects of trade tensions and tariffs or are considering taking such actions now.

Companies have diversified both upstream and downstream, sourcing new suppliers and markets for their goods. Study participants indicate their focus is now more on downstream diversification by identifying new distributors and markets for their products. Those initiatives have included new strategies, such as exporting first to a “hub country” and not shipping directly to the U.S.

While many have already diversified upstream, about a quarter of respondents still look to such initiatives to build supply chain resilience. South Asia, and India in particular, has been the most targeted area. In Southeast Asia, Vietnam and Indonesia top the list. Companies also cited Mexico, Poland and other countries as targets for diversification strategies.

As a treasury official from a Chinese metals and mining company put it: “Not just our company, but the whole industry has made plans to diversify supply chains into ASEAN, Latin America, Africa, and Middle East.”

Asia-based corporates hold off on price increases—for now

At the time we conducted interviews for our study in Q2 2025, only 5% of large Asia-based corporates had raised prices because of tariffs or said they planned to raise prices in the next six to 12 months. We believe there are two reasons companies were holding back from raising prices then—and why many continue to do so.

First, on average, corporate balance sheets are strong across Asia. Balance sheets are so flush that corporate borrowing has slowed, with companies opting to fund investment and expansion with cash reserves instead of credit.

Second, these strong balance sheets have given companies flexibility. Trade rules and tariff rates have been in a near-constant state of flux. Without any certainty about what final tariff rates would look like, companies generally took the decision to absorb tariff costs in the short term as a means of preserving customer relationships and market position. With healthy balance sheets, companies could afford to take the hit and wait and see the ultimate outcome.

Unexpected benefits: Lower prices in some Asian markets

Between 10% and 20% of large Asia-based companies aren’t sure how tariffs will impact their businesses in the next six to 12 months. That uncertainty should not come as a surprise, given the broad and sometimes unpredictable ramifications new tariffs are having on global trade and the economy.

For example, a treasury official at an Indian electric utility believes that, “The tariffs may work out positively for us because we are getting cheaper raw materials from China.”

That sentiment was expressed by other large corporates as well. As companies in China and other countries hit with high tariffs divert goods to markets with more favorable trade terms, increased supply in those new countries is driving down prices. This is true for raw materials that companies use as inputs in manufacturing their products. It is also true for some consumer goods—especially since the Trump administration moved to close the “de minimis” loophole that allowed packages worth less than $800 to enter the U.S. duty-free.

Unintended consequences: De-dollarization gains steam

The risk of overreliance on the U.S. financial system and dollar-denominated trade and settlement are now being taken more seriously than ever before. Specifically, multiple large companies participating in our study said new U.S. policies were prompting them to consider de-dollarization. “We are actively seeking suppliers from other countries. Also, we plan to de-dollarize our settlement currency,” said a treasury official from a large Chinese corporate in the marine industry.

De-dollarization has been a popular topic of conversation since the first Trump administration. For the most part, however, those discussions were viewed as long-term in nature. Few observers expected rapid movement away from the dollar.

U.S. trade policy has changed that dynamic to at least some extent. The U.S. administration’s aggressive stance with many countries has created a perception among some businesses that the U.S. financial system can be weaponized and that complete reliance on the dollar leaves them at risk.

Second-order effects: U.S. banks losing traction

U.S. banks have lost ground in Asia trade finance since the U.S. began imposing tariffs on China in 2018, especially among Chinese corporates.

Of course, there is more than one reason that a large Asia-based company might switch from a U.S. bank to another provider for trade finance services. First and foremost, Asian banks have been building out their own capabilities and winning corporate relationships.

As recently as 2017, only 68% of corporates headquartered in Asia used an Asian regional bank for trade finance, and only 30% named an Asian bank as their lead trade finance provider. By 2025, closer to three-quarters (73%) are using an Asian bank for trade finance, and 37% name an Asian bank as the lead provider.

Over that same period, the share of Asia-headquartered corporates using a U.S. bank for trade finance dropped from 31% to 23%, with a corresponding decline in lead provider status.

It is no coincidence that the loss in market penetration by U.S. banks was driven by a pullback by Chinese companies. In 2017, roughly a quarter of Chinese corporates used a U.S. bank for trade finance. By 2025, that share had dropped to 14%. That shift reflects a clear and intentional decision on the part of Chinese companies to scale back their relationships with U.S. banks following Trump’s imposition of tariffs in his first term.

What does all that mean going forward? For the most part, Chinese companies have played their hand. With U.S. banks’ market penetration falling so low in China, there is little more that Chinese companies can do to reduce their exposure. Looking across the rest of Asia, it seems that large corporates are not making any knee-jerk decisions based on the latest round of tariffs. From 2024 to 2025, the share of Asia-based corporates using a U.S. bank for trade finance was stable, at 23%.

It remains to be seen how the position of U.S. banks changes in the future, if tariffs alter trade flows and large Asian corporates devote more attention to intra-Asia trade, Europe and emerging trade corridors such as the Middle East and Africa.

How can banks help companies navigate tariffs?

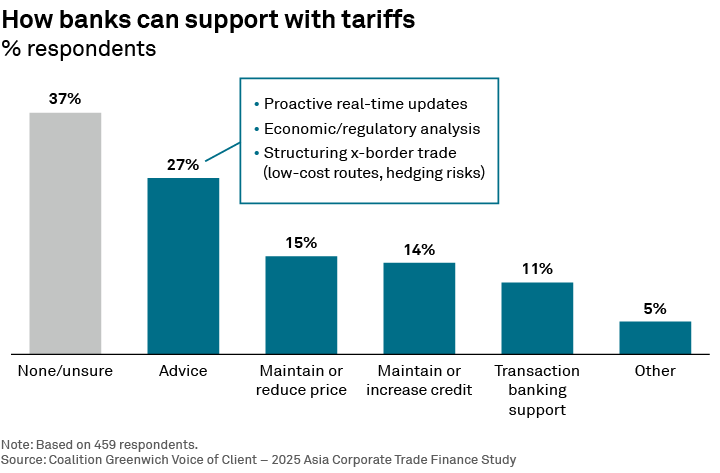

Uncertainty around tariffs could create opportunities for banks to deepen relationships by helping Asia-based corporates navigate this volatile period of change.

The large companies participating in our study say the best way banks can help them steer through tariff-related challenges is by providing timely advice and consistent support in the form of affordable credit.

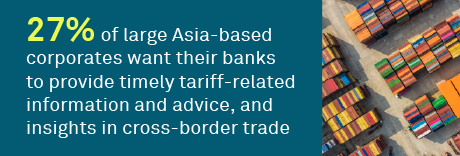

More than a quarter (27%) of large Asia-based corporates want their banks to step up and provide tariff-related information and advice, including proactive, real-time updates, economic and regulatory analysis, and insights on hedging strategies and other aspects of cross-border trade.

Companies are also seeking support and flexibility from their banks in trade credit. As the representative of one large Asian company put it, “Firstly, banks should keep their credit commitment and make sure we can get funds when we need them. Secondly, banks could share updated information with us [on things like] FX trends, market situation, cross-border transaction, and settlement policy, etc.”

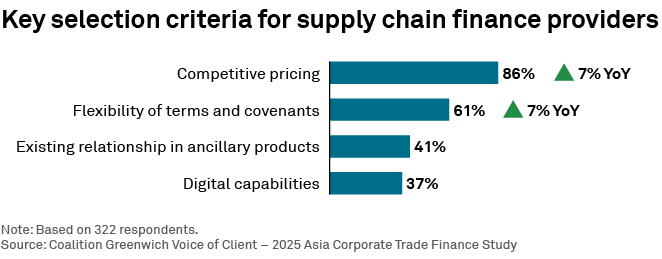

This requirement for flexibility is echoed in supply chain finance. From 2024 to 2025, as tariffs took effect, the share of large Asia-based corporates citing “flexibility of terms and covenants” as a key criterion in their selection of supply chain finance providers jumped seven percentage points, to 61%.

Tariff upheaval slows trade finance digitization

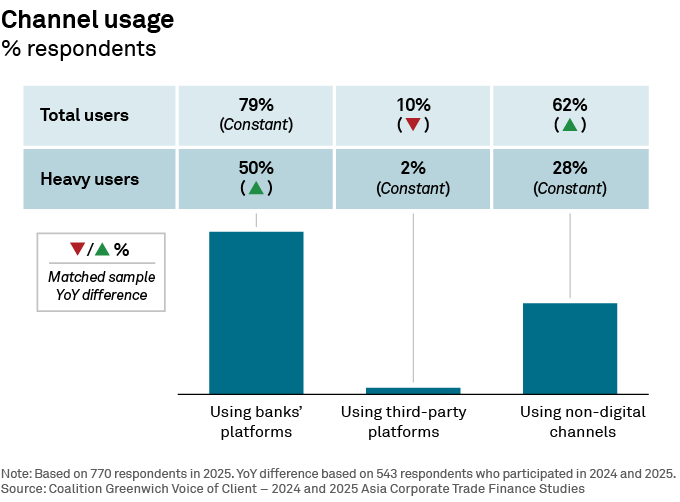

The process of gradual digital expansion in trade finance took at least a temporary pause in Asia this year. As Asia-based corporates worked to understand and digest the impact of new tariffs, the share of companies turning to non-digital channels for trade finance increased to 62%. That shift reflects companies’ demand for reassurance that their banks are there to support them and for the type of tailored advice that can’t be delivered through a digital platform.

Relationship Director and Head of Corporate Banking—Asia and Middle East Ruchirangad Agarwal, Elijah Lim, Wesley Han, Delia Phua, and Pushpak Vanjari specialize in Asia corporate/transaction banking and treasury services.

MethodologyBetween April and July 2025, Crisil Coalition Greenwich conducted 789 interviews with corporates with annual revenues of $500 million or more across China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Macau, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam. Trade finance interview topics included product demand, quality of coverage and capabilities in specific product areas.